Performative circumstances in Kalabhavana

Essentializing “everyday”/ spatial discourse/ Theatre in an Art-institution Based on experiences during 2000-1005

The following article was published in the Art & Deal, Issue No. 31 - Radical: Possibilities / Ruptures, April 2010, Edited By Siddharth Tagore, Guest Editor: Rahul Bhattacharya. http://www.artanddealmagazine.com/test.aspx

Samudra Kajal Saikia

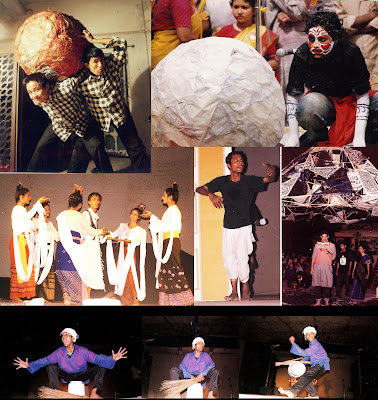

Fig. 1,

performative circumstances in Santiniketan, various occasions, clock wise: 1. a moment from Briksha-Ropan, 2. Fun-Games, a theatrical exploration by students, 3. A scene from Jertuki Bai, 4. Outing of Kalabhavana at Sonajhuri, 5. Santhal dance in some festival in neighbor village, 6. Haradhan Baul singing in the campus.

A walker on the street, who is a voyeur, who peeps at other’s (social and private) lives, breaks the theatre-architecture. If we consider a street walker as a theatre-spectator, than, the theatre takes place on the street. The spectator, who was buried in darkness in an auditorium, the spectator, who was bound to seat one particular seat switching off his mobile phone – just forgetting his fellow spectators, the spectator, who was dumb (and hence deaf) in the theatre hall, is now free on a street. He can move, he can whistle a song; he can become a part of the scenario. No more is he deaf and dumb. He feels inferior no more, because he knows he is a part of the “silent majority” of the insignificant little men . He is no more the God having a celestial eye, grasping the scene through a renaissance window offered by a proscenium theatre. He is an alert and active spectator of the street. The power in case of this theatre not in the architecture, but, insisted upon the bodies.

Performance takes place in Kalabhavana campus just like that. Kalabhavana-theatre (student-activities in Santiniketan) intervenes in the realm of theatre and performance with everyday-nuances formally and structurally, and in the same time it also intervenes in the ‘everyday’ with some sort of theatricality. So, a two way effect is visible.

Fig. 2,

The campus on any ordinary day

The political consciousness of representing everyday life we find in contemporary plays is not found in Kalabhavana theatre activities. But it tends to the everyday by its structural exploration and its presence. Primarily Kalabhavan-performances raise issues around oral statement and formal execution, content-conscious construction and practical modulation and so on. We can certainly stretch it to the matter of verbal declaration and behavior and on the way we can remember Mukarovski’s two kinds of signs as: communicative sign and autonomous sign .

When I say about Kalabhavana performance, it is somehow different from the Santiniketan theatre traditions. The Santiniketan theatre contains two distinct kinds of practice; first, the Santiniketan tradition of Rabindranath Tagore’s plays in various ashramik occasions; and the folk based musical programs (including Baul-Fakir song, Santhal festival of neighbor villages). The history of Rabindra-natak tradition could be traced from the Vichitra Sabha in the famous Calcutta Jorasanko Thakurbari which flourished in Santiniketan in the Golden days of the artists like Ramkinkar Beij and others. The modernist proposals of Rabindranath (behind the establishment of Santiniketan) are, somehow, inherent in those theatre practices as well. The theatre tradition turned the space of Santiniketan to a cultural whole, rather than a mere institution of fine-arts. Other than the tradition of Rabindra natak and the frequently happening musical performances by the Bauls and the fakirs one also encounters with most vivid but ordinary everyday-events in Santiniketan. While saying about the “performative circumstances” in Santiniketan, these events are to be accounted. And in Kalabhavana campus, we come across to some other features.

JUST LIKE THAT…

Fig. 3,

Three students in an ordinary but theatrical moment, The Chairs: the Private and the Public, inside the new building of Art History Archive

A boy keeps sitting under the Chatim tree for several hours, doing nothing. Sometimes he sings a song just for nothing. One gets bored with life since nothing is happening. The other is excited for so many things happening at a time. A baul singer came and sang songs last evening. Some artist student displayed the life size sculptures there, outside the studio or classroom. Somebody hanged a poster on the canteen wall at late night without leaving a trace of who did it. As a symbol of protest against some political issues, somebody made an installation on chatal . In the morning there was a thrill around it. Somebody cries behind the Karabi tree. Somebody shouts at the boys’ hostel. Still the evening is so silent. A cry of a crane at the museum breaks down the silence in the midnight. Still everything is so available and so familiar that, one is bored for nothing is happening. For putting a poster on Mama’s canteen, for installing something (of course with visual sensibilities) at the chatal, for exhibiting a sculpture open-air, for singing a song under the chatim tree nobody gets a multinational grant. Nobody is felicitated for that, neither anybody is going to keep in mind the event after a couple of days. But things are taking place. Why? Just for nothing. These small events taking place ‘just for nothing’ can insist us for some discussions around performance and theatre.

*

Fig. 4,

(a) The chatal with installation and the Mama’s Canteen with temporarily painted mural in the time of Nandan Mela

(b) The chatal in the time of a performance

Nandan Mela, an annual art-fair of Kalabhavana offers immense possibilities to the students to deal with performative activities inside the campus. Most importantly, Nandan Mela stands in the interface of the institutional space and the public domain. The grand execution of the mela (festival/fair) invites the ‘public’ inside it and loosens the canons of disciplinary practice of art making. Secondly, the performative practices of Nandan Mela are always spatial, space specific by the nature of the Mela. Though it is grand in nature, the claustrophobic characteristic of grandiose cultural production system is not observed there, hence an experiential interaction of the spectator and the performer is possible.

In the evening of Daul Purnima thousands of public gather at the place named Amrakunja and have a procession singing a song from Rabindranath: O Amar Chander Alo… Under the light of full moon the chorus of the multitude, where every individual becomes lonely within the crowd, and at the same time each and every individual contains within the self the essence of the crowd, creates a tremendous effect. Just allowing the self to be lost among the huge crowd one cannot remain un-surprised thinking of the power of the metaphoric large in contrast to the insignificant singular. At the same time one cannot escape from the tension between the power of an institutional construction which provides the space, festival and occasion and the spontaneity and autonomi-ty of the creative act. Such kind of practices (what the Santiniketan people calls Baitalik) contains the greatest mode of performativity that ever any kind of art form could create.

On the 3rd of December, (birth anniversary of Nandalal Bose), after Nandan Mela, all the Kalabhavana associates gather in front of the art-history department at the early morning just before the Sun rises, and moves singing Rabindra Sangeet towards Nandalal Bose’s house, circumambulating the Santiniketan campus with burning candle lights in their hands. The candle lights or the white dress-code is determined, but, the order of movement is not determined. Yet nobody can walk hastily, neither can move slower there. The movement comes under one particular order by its very nature. One may feel or may not feel but the presence of some institution (not essentially Santiniketan or Viswabharati) is there.

The moving peoples actually fulfill a certain sense of aesthetics through a process of essentializing an order. From that order one singular cannot escape, cannot remain aloof. A spectator of that moving crowd unknowingly becomes a part of that even if s/he is not moving at all. If there is any “little” person with inferiority complex, he or she may become much littler in front of the bigger movement, for a tiny part of moment. But at the very next moment the bigness of the crowd enters into that singularity. In case of these moving crowds singing particular one song or following one similar kind of movement may not be well rehearsed or similarly well drafted. Yet the crowd by the very nature of a crowd includes all the haphazard disorders under one particular order. Nobody can escape from that order.

But that instantaneous (not well-drafted) order itself is a disorder in the order of everyday life of a singular-individual. A huge crowd moving towards one single direction cannot be an everyday phenomenon as such, but it pretends to be. It pretends ‘to be’ for everyone by his/her essential uniqueness, his/her inherent body movement, ‘walk-cycle’, inferiority, superiority, pride, guilty, comfort, disgust, mannerism, speed, sneeze, yawn, hiccup, anger, turn-around, making face, laughter and just-for-nothing-sadness contributes to that ‘order’. Nobody can make a protest within it.

For various performances we used the procession for its above discussed characteristics. In a performance in Nandan Mela 2004, a group of performers made a procession singing a song and entered into the crowd of Nandan Mela. The performers singing a song were carrying a huge piece of blue colored cloth arrived at Chatal and crowd gathered around along with their “autonomous” or “instantaneous” movements wishing by their gestures to “happen something”. What did the crowd exactly wished to see or what the performers intended to show? Initially there were the wishes to see and to show, but after a few moments everybody in the crowd realized that the movement itself was a happening, the crowd itself was responsible to make it entertaining.

In the name of Jagajhompo, students prepare a play which is actually a farce, and always contemporary in nature. It ridicules some current issues with witty humor and adopts a style of the Yatra theatre in a subversive manner. Other than Jagajhompo, the other performances taking place in other places constantly break the parameters of art and cultural production.

Naveen-Baran, the welcoming ceremony of the new-comer students is another phenomenal cultural event where mostly the students from outside try to portray the multicultural aspect of the place. There is another event named “outing”, where people go out for a picnic to the (Sonajhuri) forest nearby, singing along the streets. This attempt has significance for trying to inculcate the habit of singing songs in the everyday lives. Here, we see, singing song is no more phenomenal, no more comodified object, no more a logocentric product/object/thing but an live experience. The baul and fakir singers most often coming to the Kalabhavana campus also try to do the same. After each and every institutional occasions, students celebrate a ‘campfire’, an evening with singing and dancing, again attempting the same.

All the departmental houses are situated in Kalabhavana in such a manner that a vivid interaction among the departments is already provided by the spatial arrangement. Most profoundly the boys’ hostel campus is within the institution space and the entire studio remains open for twenty-four hours. In fact there is no boundary or formal gate-way for the campus. And as a result the students’ personalized living and institutional activities are merged. Again in various occasions in the year all the students, stuffs and outsiders gather and engage in some creative activities: like in seventh July on the occasion of Briksha-Ropan, ornaments from tree leaves and flower petals are made and the campus decorated. In each and every occasion singing Rabindra sangeet and folk songs is common. Most of the times such activities turn to some performances with theatrical features.

Fig. 5,

Various activities of a Briksha Ropan festival, 2009, inside and outside the campus

Fig. 6,

A mobile interactive performance in Nandan Mela, 2003, The Blue Cloth, with instant improvisations.

Let me mention some of the numerous theatrical executions in brief. From the platform of Samakal Rabindranath’s Bisarjan, Maxim Gorky’s story Danko and performances based upon Somnath Hore’s autobiographical chronicle Tebhagar Dairy and Ramkinkar Baij’s interviews Mahashay Ami Chakhkhik Rupakar Matro are mention worthy. The last two were under Parnab Mukherjee’s guidance and the last one was reworked and performed under Taufiq Riaz’s guidance, at Birla Academi of Art and Culture and then at Gaganendranath Pradarshashala, Kolkata, in a theatre festival (it was renamed as: Je Torey Pagol Bole).

Among the plays initiated by me Tezimola, based upon an Assamese folk tale in 2001 at Natyaghar Santiniketan was musical, minimalistic with less stage prop and a proper proscenium format. The other play based upon Assamese folk life was Jetuki Bai which was basically a solo performance performed by Taslima Akhtar in Nandan Mela, 2002. Total four productions were experienced in various locations (including one indoor and three outdoor spaces and one at Kala Mela, Birla Academy of Art and Cultures, Kolkata). Total three major solo-performances were designed during the time of 2000 to 2005, second was Ophelia, and then Neha’s Santa Claus. The play we experienced for several times in various places with various stylistic explorations was Where Has the Ghosts Gone. It was a script which was extensively explored as one-person performance, two-person-performance and group performance in several places including a metropolitan space like New Delhi (National Theatre Festival organized by Abhivyakti, IP College for Women), outskirt of the city like Baidyabati (near Kolkata), in some local cultural group organizations like Guwahati Artist’s Guild and CPI (m) office (in Guwahati) to a remote village in Ruppur (organized by Shwahid Smarak Samiti, Bolpur)…

Here some visuals from one of the performances of Where Have the Ghosts Gone will offer an idea about the ambience (see fig: 11). The core performance was of almost twenty minutes only but the canopy-like collaged cloth hanging above was made for daylong not only by the performers but by several peoples. It was a part of a day-long outdoor workshop in Kalabhavana and the cloth was in the process of stitching (like Kantha, a collage of wasted rags), and whoever passes the place was asked to join their hands. Basic performance was by two actors (Roshni Ravindra and me) but two narrators helped the narration from behind two black-board easels. The performance was within an academic space and as most familiar object of an academic space the use of those easels was logical. At the end of the performance the audiences were offered some balls made up of ropes and threads and were asked to throw to the canopy. The ropes and threads thrown by the audiences made a haphazard rope-construction in the space. This metaphorically stitched or sewed the whole space block. So no audience remained alienated from the actors neither from the performing space.

Fig. 7,

Various theatrical experiments during Naveen Baran, Nandan Mela, Basanta Utsav and any other ordinary day.

Fig. 8,

Theatrical adaptation of Vadki, a short story by Bhhupen Khakar. Designed by Sanchayan Ghosh.

Epilogue: Troubles in doing/mapping theatre in Santiniketan

There are a lot of questions following, like: Are they ought to be discussed as theatrical exercises or as an extension of their (the students’) visual experimentations? Should we explain the evidences as contemporary amateurish practices or just treat them as mere student activities? What a lineage do they trace, from the avant-garde tradition or from any traditional space? Are they non-conventional by nature/circumstance or for some subversive political insertion? Above all, do they belong to the visual art domain or to that of the performing arts? Here are some of the major concerns for the troubles in mapping (as well as doing) theatre in Santiniketan:

Crisis in theatre emerges when a drastic economic change happens (economy overwhelms the belief), when too many outsiders (non-believers) enter into a geographic location, or too many mediumistic proposal becomes available (offering a question of where to believe). In a multicultural multilingual sphere the nature of the “believer’s community” is different from a homo-cultural space. In Santiniketan it appears as a severe issue to appropriate a theatrical device. Perhaps the strategies of the Tagorean ideology behind making a space like Santiniketan fulfilled the criteria of producing a common taste of spectatorship through the numerous ‘innovative’ festivals. But the multicultural phenomena of Santiniketan (a considerable number of students are there from outside the state and the country) is a problem for adopting a homogeneous taste of cultural production. More than the ‘mainstream’ theatre of Santiniketan, the day to day activities, public gatherings and some homogeneous ‘taste’ in diversity draws a spectator’s attention more. Considerably, neither this place belongs to a metropolitan/city ambience nor inherits the characteristics of a rural habitation. At the same time it resists the mufossil characteristics of its surrounding areas Bolpur, Suri or any other nearby West Bengal mufossil town possesses entirely different characteristics. So, ultimately Santiniketan, the location gives us an Archimedean space to judge all the rural-suburban-urban spaces.

So we can see, though very much close to our everyday, the performative aspects of kalabhavana Campus are outside of all the norms that could make them worth-studying. Even if sometime they are a part of the Santiniketanian customs, there is an inherent denial to the tradition in the kalabhavana activities. Initially I was claiming that they lack the documentation, and hence a sense of historicity. But by the time we realized that, only for the ephemeral nature of those activities, the lack of authoritarian value and for the tangibility they could sustain the subversive essence even being inside an institution; what the Aashramic Festivals (traditional activities maintained by the Vishwabharati) could not.

Fig. 9,

Mahashay Ami Chakkhik Rupokar Matro, a performance on Ramkinkar Beij’s interview, under Parnab Mukherjee’s guidance.

Fig. 10,

Scenes from Ophelia, in the Campus.

Fig. 11,

Moments from a production of Where Have the Ghosts Gone, at Ramkinka Beij’s Birth Centinary Opan Air Workshop.

Fig. 12,

Views from the Kalabhavana Campus in various ‘ordinary’ times of the year.