A chapter from the dissertation paperResiding in the Shifting Spaces an Attempt to Conceptualize the

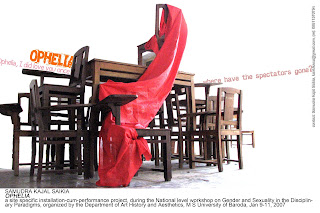

“Spectator” by

Samudra Kajal Saikia

Migrating/travelling with Ophelia

An encounter with the conceptual spectator

Representing Ophelia

Destruction

of a gaze

My

rendering of Ophelia in Santiniketan

Ophelia

in Baroda

Thing and not-thing

Director v/s Curator and performance Art v/s

Performing Art

|

What was my first day in theatre?

Perhaps, it was the day of separation, the day I lost

my mother tongue and made myself into a foreigner, in a country which was not

the country of my birth.

Eugenio Barba, Beyond

the Floating Islands (New York, Performing Arts Journal Publications,

1986)

There

are no universal values in the theatre. There are only personal needs which get

transformed into social and political actions, rooted in the individual

histories of theatre. ….but in his theorizing of cultures on a “transcultural

level, there is a universalizing tendency that diffuses the historical differences

permeating forms, resulting in a Eurasian encapsulation of “laws” and “rules of

behavior.”

Rustom Bharucha, The Theatre of

Migrants (Theatre and the World; Essays on Performance and Politics

of Culture (Manohar Publications, 2/6 Ansari road, Daryaganj, New

Delhi-110002. 1990

Hamlet, by William

Shakespeare was written in 1600-1601. And during this time span of more than

400 years Ophelia, the character from Hamlet is being represented

exclusively all over the world not only in theatre or theatrical performances.

Neither is she limited to literary fictions. From visual arts including

painting, sculpture, graphic print to commercial media like photography we get

Ophelia’s resounding presence. Thousands and thousands of Hamlets

are produced all over the world in the last 400 years. (Among the most

contemporaries, we enjoyed Hamlat, the Prince of Garanhata in

Kolkata theatre by Swapnosandhani, and Rajkumar Hemendrajit by Baa

in Guwahati. In the first one Ophelia or Shefalika was a sub-urban lady in a

place named Garanhata and in the latter Ophelia was a North-eastern hill-tribal

lady.[2]

Now

let me ask how and why Ophelia became such an exclusive subject for all these

fictionalizing efforts. I’ll try to concentrate on visual arts. Perhaps it is

well known to all that the emergences of Ophelia as a theme was historically

prominent in the Pre-Raphaelite phase of painting. For the romantics it was a

most adorable theme. In the visuals I have collected we will see in all the

visual depictions Ophelia actually came far away from the Elizabethan

Shakespearian character of hamlet. Every artist is presenting/representing her

in his own individualistic, personalized style. But a train spotting look makes

us aware of some sort of similarities also all through these numerous works.

If

we search for the HOW and WHY behind Ophelia’s immense popularity these issues

would spring up at the first hand; gaze, body, representation, gender,

sexuality, madness.

First of all a simplistic answer is: the character of Ophelia is ever fulfilling some basic needs of “visual arts” through the history. It satisfies the established overarching patriarchal hegemony of painting. In all these visuals what is Ophelia, reclining woman, and nothing. So more than who is Ophelia, what is Ophelia is a more relevant question in this case.

|

| Millais’s drawing for Ophelia |

|

| Delacroix’s drawing for Ophelia |

First of all a simplistic answer is: the character of Ophelia is ever fulfilling some basic needs of “visual arts” through the history. It satisfies the established overarching patriarchal hegemony of painting. In all these visuals what is Ophelia, reclining woman, and nothing. So more than who is Ophelia, what is Ophelia is a more relevant question in this case.

Definitely

Ophelia is not only an object. It is portrayal of a character from Shakespeare.

Character, dramatic character, itself already means somebody personified and

subjectified. So, in one sense all these visual depictions are essentially

repersonified and resubjectified. But an intense observation can prove that,

Ophelia as a theme of painting actually satisfies some particular genre of

tradition. For example, like any other genre of visual depictions, mother and

child, still life, landscape, portrait; reclining woman is also just a genre.

As thematic, its appropriation in painting is understandable under these

following categories:

1.

reclining woman

2.

sleeping beauty

3.

female body

4.

nude

5.

melancholia and

madness

6.

imagery of death

7.

under water,

etc.

Destruction

of a gaze:

Now

another question: why a spectator feels comfortable in front of a painting done

on Ophelia? By no means has it carried any comfort ability in its thematic.

Under the pressure of the social system, and because of the effects of some

kind of verbal masochism of love affair a teen aged girl becomes mad and

consequences to death. But in both its thematic and visual representation a

spectator feels comfortable.

Most

of the cases, Ophelia’s face does not look back to a spectator. Her eyes are

either shut down to show her death, or, they are downward signifying her

melancholic mood. If the eyes of any Ophelia figure looks back to you, the

spectator, it is again not self-asserting at all. Those eyes are lost in

themselves indicating either her innocence or her insanity. So as a spectator

you have not to confront any other’s gaze. You are not bound to apologize

yourself in front of some other’s gaze. Some other’s gaze does not yet seizes

you, but you can easily seize that particular other’s body and simply can you

move from one painting to another.

So

clearly, portraying Ophelia means killing an object’s gaze, the object you are

looking at.

Now

what does this destruction of an object’s gaze mean? It means the power of the

subject over the object. Secondly it means it is ready to satisfy somebody’s

masochistic pleasure. This destruction of gaze is highly satisfactory to the

male-dominant system in the history of modern painting, because at the first

gaze before the object in the picture speaks something, a spectator speaks out:

she is mad, she is innocent, and she is dead…

Drowning Durga,

a most commonly appearing visual in the publications at the time of Durga

puja

Ophelia

was first planned in December 2003 and staged in a national campus theatre

festival, organized by Abhivyakti, New Delhi in Februari 2004 and then

in Kalabhavana, Santiniketana in 11th March, 2004.[3]

The

initial attempt tried to grasp what Millais tried (fig. 79) to do in the

pre-Raphaelite phase of painting and what were the sufferings of Shakespeare’s

Ophelia as an innocent girl very much loyal to the family. That Ophelia,

enacted by Roshni, a girl from Bangalore

The

binary discourse my script on Ophelia tried to address was very much

comfortable in a proscenium format. The proscenium division of the performing

space and the spectator’s seat also resembles the oppositional power operation

between two distinct entities. As I mention again and again, it maintains the

same mode of an Alberti’s window viewing painting which offers a spectator immense

comfort. I am saying about some ‘comfortability’ of grasping or visually

seizing something with voyeuristic pleasure. That is why the destruction of

a gaze what I explained with regard to diversified representations of

Ophelia (and also to Durga immersion, I felt, would be most appropriate in a

proscenium format only. Otherwise I was under questions for: at what time we

were practicing non-proscenium third theatre forms (under the influence of Samakal),

where the Santiniketan physical space provides no proper scope for a stage play

– technically speaking, the actor Roshni too was not comfortable for a typical

stage play; why was I planning something in a proscenium format.

The

mise-en-scene made for Ophelia, the frontality of it; the

perspective and the use of light make a spectator feel it is all about “There”

not “Here”. Either it can produce some sort of desire “just to be there” or can

offer a spectator this comfortability that “it is just about somebody else, not

about us. That lit-up space is different from ours, which is buried in

darkness, and we are safe for that place would not penetrate our place”.

And

here in the picture we can see how we can destruct the gaze easily in the

proscenium mise-en-scene and in case of the next picture we can voyeuristically

enjoy some other person’s interior.

Ophelia

in Baroda

But

here in Baroda

It

was fragmented, not out of any fascination, but due to some obvious

circumstances. As a part of a multi cultural academic institution, neither

could we submit ourselves to any grandiose theatre tradition, nor could we

belong to any traditional theatre space. Let us explore this very ordinary

space and see if it becomes performative or not.

After Delhi

Mahananda, a girl from the department of English

(originally from Orissa) who never enacted any role in any play before, came

forward to take the challenge of portraying Ophelia and Sadh Nawab from the

same department for Hamlet. Though those two characters were there and the play

was based basically upon their relationship, in our performance they had no

direct communication as such. Two characters were separated entities, almost

like a compilation of two monologues or two solo-performance pieces. This

separation of the two characters became more affective and more powerful for

their melancholic psychological status, historically and socially determined

hierarchical isolations and ideological differences. This time Ophelia appeared

much more aggressive, violent and self-assertive who refused to die. Instead of

submitting herself to death, allowing the spectators to destruct her counter

“gaze” she directly looked at the audience.

Though Kalabhavana in Santiniketan and Fine Arts

Faculty of Baroda are two major art institutions of India

But the design of Ophelia was not

bearing essentially any local dialect, but inherited some sort of

avant-gardesque characters. Again it was a script derived from a Shakespearian

play celebrated world wide, and thus also inherited in the same time some

‘universal’ characteristic. It was also in a proscenium format, and, we know

that last one hundred years history of so called ‘modern’ Indian national

theatre tradition have given birth to the “universal” spectator to the

proscenium theatre. Wherever we go with a proscenium play we will get that ‘universal’

or ‘celestial’ spectator. Or in other way around, that ‘celestial’

spectator is prepared to see any kind of proscenium play in the nation (in the

world). It proves that we did not have to think over the preparation of a

spectator.

Thing and not-thing

Other than that, some basic problems were shared by

the both places: like the problems out of transculturalism, or of standing out

side the social space (no rural, no urban, no mufossil, no city). Under such

circumstances I do not prefer any technique of preparing my actors leaving them

to think of the play as an offering. I can not make a product, neither

can I make this product saleable. There is no scope to bring this

theatre to any national theatre festival of any metropolitan city and no

promise of re-producing it. In place of being a producer (giver), under such

circumstances I prefer to treat myself as a receiver only. I can put more and

more time to prepare myself and my actors, not for a product, but

for instantaneous improvisations: which will explore what is hidden in their

psychology, what is the demand of the physical space and what makes a behavior

to an action. As many directors like to think of a play as an ‘offering’ (which

historically started with that kind of spirituality, Stanislavsky and

Tolstoy used), as if the actors offering something to the audience, and try to

make a hypocrite acknowledgement of the greatness of the public within which we

can clearly see their strong narcissistic individual “ego”; I can not think

about that kind of ‘offering’ to the public. Only I can provide (here also is a

sense of superiority of providing somebody something, we can not simply escape

from it) a space for some actors (who are action-makers, not any “thing”-maker)

who are basically context-providers rather than content-providers[4],

and wait for the eye-witness spectators if the action makes any sense for them

or if they add any sense to the action.

As a result, the experience of Ophelia

in Baroda

Director v/s Curator/ performance Art v/s Performing

Art

|

| a space for pre-play activities, which stands in between performance art and performing art. |

In front of the department of Art History on the

courtyard there was an arrangement of some buckets full of water with blues as

if was to wash cloths under an over-head rope construction. At a particular

time my mobile phone rang and I announced it was a time to start and people

gathered from all the sides. I started to clap in a particular rhythm and asked

the gathered public to join my clapping and quite astonishingly all the

gathered public started to clap in one particular rhythm. In the very beginning deliberately I refused

to call myself as a director but a curator who provided a space

to a few individuals to work on under given circumstances. In fact the actors

were given freedom to portray the characters as their imaginations as well as

more than personification or character-portrayal an intense study of the

ambience was given priority. Though it was instant decision, yet contained some

deliberate intensions. The arrangement of buckets, cloths, blue, and the rope

construction over head appeared like an installation (which was under visual

art domain) rather than any theatre set (which was not under the so called

visual-art domain). Again whatever was happening there was very much a happening,

or not-thing activity (which could claim itself as a performance art,

again an object of study under visual art domain) rather than any well

rehearsed form of performing arts (which were not a part of the so

called visual arts domain). There is a crucial division between performance

art and performing art. Both are ephemeral and space-time

specific, both are live and communicative, yet one stands

inside the studies of visual arts and the other remains outside. One deserves

the high, elite, bourgeois nature of making an art-thing (though they claim to

be not-thing as such) and remains available to the limited targeted spectators

whereas the latter usually remains open to the larger number of public as

audience. One gives much more importance to the documentation and the

reproduction of the documents, whereas the other form thinks that the

documentation can not deserve the essence of the live art-form. Whatever it is,

the narcissist actor is inevitably present in both of the cases.

However in the rhythm of the audience’s clap one student Namrata sang a subverted Bob Dylan song and we started washing white cloths in blue water. In the ambiance white colour was emphasized allover. After our request many people from the audience without any hesitance started to dip cloths into blue water and to hang it in the rope construction above head which eventually came down with the weight of the wet pieces of cloth. After the cloths were hanging the visibility of the ambiance was drastically changed.

In

the next step Ophelia (Mahananda) started to lit up candle lights around a

basin where a doll of a nude girl (as if some arrogant child put his/her

violence upon it) and some paper-boats were floating with a poem:

You said the time is cursed[5]

But my love is cursed by

time

And I am cursed by my love…..

Then another girl, Namrata woke up from a stuff of

fallen leaves with murmuring sounds in a different darker place and starts

singing. From the darker place in the courtyard Namrata moved to the porch area

in front of the department of art history and following her audience also

entered in to the area and takes their seats. Till now the audiences were

confused where to stand or what to see, now they are getting an orientation

made by some symbolically arranged seats and the light effects. And from here

the semi-proscenium effect began with Hamlet the Renaissance man, the man of

scholar emerging from a huge news paper carpet saying blab blab blab….

resembling Heiner Muller’s Hamletmachine and words words words referring the

original Hamlet play[6].

Almost like a prologue Hamlet (Sadh) gave an overview of the mode of the

forthcoming performance and indicated the multiplicity of reading a

Shakespearean character in our times. He also uttered referring Jean

Baudrillard: Words are devil demon. Images are devil demon[7]

and just then hundreds of visuals

from Ophelia’s representation all over the world from painting, photography to Hollywood movies projected on the background to obsess or

exhaust the audience with images.

In the

meanwhile some information of Ophelia was given to the audience along with the

author’s subjective response to it.[8]

As we constructed the castle in Ophelia in Santiniketan with

plastic electric wiring pipes this time we constructed it with stretchers or

empty canvas frames joint with each other which provided some moveable folding

structures. Those structures in each arrangement took new shape and resembled

to castle, closet and even Ophelia’s coffin.

As the canvas stretchers used material for

improvised stage-prop were very much familiar in the campus of fine arts

faculty, keeping in mind of the academic sphere and the referential subtexts of

the meta-text, the background was full of words written upon cloths, acrylic

sheets and walls. (Remember, the core performance was started with “Words

words words”, Hamlet, Act II, Scene II), and similarly there was

another space created for acting-zone designed with classroom chairs. To

mock the intellectual narcissism of the protagonists from Christopher Marlowe’s

Doctor

Faustus,

Shakespeare’s Hamlet to Goethe’s Faust, and to essentialize it within

an academic space that chair-construction was relevant enough.

Making a critique through his gesture of the

narcissist actor and the “modernist man” Sadh appeared as Hamlet with a helmet

in his hand resembling the human skull of the graveyard sequence[9] of

Shakespeare’s Hamlet. “Hi! I’m

Sadh, but for this time let me be Hamlet once again. Not the Hamlet of 1600 AD

but a Russian Hamlet of Boris Pasternak[10],

1946.”

This

time the actor through the audience space went to the Chair construction behind

the audience and climbed up reciting Boris Pasternak. From Boris Pasternak to

Istavan Tzabo’s Mephisto (what we discussed in the second

chapter) to Heiner Muller’s Hamlet Machine he referred and

essentialize the egoistic problem of an actor provided by our times.

I’m

Hamlet, a performer. So I’m bound to undergo all the agony and ecstasy of being

a performer. Was it said by Hamlet or Pasternak, “This time release me”?

And

somewhere else Handrick Hofgen a character from Christopher Mann’s Mephisto

utters: I’m just an actor, what can I do? Why blame me?

Ophelia,

My love, your heart is beating like a clock.

No,

Shakespeare’s Hamlet didn’t say it; it was said by Heiner Muller’s Hamlet. Is

it Hamlet or Heiner Muller himself?

The

actor used the helmet as the dead-human skull and reminded the philosophized

episode of original Hamlet, the “Man” discovered by Renaissance, and dragged

the character from Elizabethan age to the juncture of Post-modernism:

I was

Hamlet. I stood at the shore and talked with the surf “blabla” The ruins of Europe in back of me. I want to be a woman.

I’m

not Hamlet…. My drama doesn’t happen anymore.

My

brain is a scar. I want to be a machine.

I

choke between my thighs the world I give birth to.

Still

I do Hamlet. Ophelia, I did love you once.

Ophelia,

I did love you once.

The

laboratory treatment with power upon a female body (with verbal

violence, with intellectual narcissism) still continues. And thus towards the

end it was a time for Ophelia go mad, but, she refused to go mad. She refused

to die. Playing with two round balls made up with white and red ropes

(symbolizing her suppressed sexual desire), in her closet, in her insanity (not

Hysteria), she entangled with those ropes. Here the performance ended.

The

tremendous ambience effect created by the audience was, just unexpectedly,

while Sadh the actor for Hamlet, moved to the chair-construction of the back,

all the “front” audiences stood up to see him properly and all the back

audiences sat down making the level of audience’s seat arrangement

up-side-down. The movement of the audiences established that they were not

passive spectators like any other proscenium architecture, in between the

polarity of Hamlet and Ophelia, the polarity of Man and Woman,

the polarity of light and darkness (or of exterior and interior,

or of intellect and sentiment). Hamlet, the man of intellect,

delivered his dialogues from the above (climbing up the

classroom-chair-construction), and on the opposite Ophelia was lying down on

the ground entangled with the ropes, and the audience remained in the middle.

So, it was understood that it was not merely a formal exercise to put the two

characters in two different oppositional places, neither was a process of

making a gimmick offering confusions the audience about which direction to see,

but, the polemic-question was addressed consciously through this formal

device. In the same time the diversified references put in a non-linear non-narrative

manner, from various sources, and acknowledgements to them by the ‘alienated’

actors denounced the polemics. Sitting or standing or moving ambiguously in the

literal gray areas (among those two performance zones the

audience-space was dimly lit up, grayed) the audiences took a position in the

whole discourse against polemics.

So,

briefly what are the premises that the experience of Ophelia in Baroda

1. It invoked the multiple reading within itself in place

of the linear way of rendering binary.

2. Obscuring the patriarchal demarcation line of

proscenium theatre it provoked the spectator that what were they seeing were

not consciously constructed something by some ‘other’ people, but somehow they

were also equally responsible for the performance along with the performers.

The way of alienating the actors from illusion was by no means similar to that

of Brechtian epic theatre, what I critically examined in the first

chapter. Neither had it tried to appear

as a laboratory product as that of Grotowski’s poor theatre, nor it tried to

adopt eclectic character and generalize the other civilizations. (See chapter

two).

3. As I mentioned earlier present

day crisis of theatre is within its own paradigm, rather theoretical than

experiential or physical. Dragging theatrical devices into a visual art

institution deliberately Ophelia could address the issue.

4. Concentrating on the essential

possibilities of a performing/performance/live art form it tried to dismiss the

disciplinary boundaries of so called “performance art” and “performing

art forms”.

5. The differed spatial level of Hamlet and

Ophelia, the detachment from each other, somehow, tried to address not a

psychoanalytical familial discourse, but the opacity of our everyday

relationships. Both the characters in the play were sufferers, beholder of

equal pathos, agonies and troubles under the similar structures: without

representing the black and white division of the power-holder and the sufferer,

it could help some spectator to talk about hegemony.

6. adjoining some instantaneous activities to the

scripted, well rehearsed play on one hand it deserved the character of a not-product,

hence non-reproducibility, and on the other hand reducing the scope of the

creator (actor, playwright, director) of “offering” or delivering a consciously

constructed “thing” or signature piece of Ideological declaration, Ophelia

addressed the power relationship of the oppositional forces that lies in our

unconsciousness.

[1] These two portions Representing

Ophelia and Destruction of a Gaze were read out in the

National Workshop for Students on Gender and Sexuality in the Disciplinary

Paradigms, held in January 8th to 11th, in the Dept. of

Art History and Aesthetics, M S University of Baroda.

[2]

Steven Bercoff imagines a secret love life of Ophelia and recreates some secret

love letters within Hamlet and Ophelia. In November 2004, Doug Huff premieres

his play Ophelia in United

States . So a reviving tendency towards the

character of Ophelia is also visible in our times.

There

is no 'true' Ophelia for whom feminist criticism must unambiguously speak, but

perhaps only a Cubist Ophelia of multiple perspectives, more than the sum of

all her parts. Elain Showalter, Representing Ophelia: women,

Madness and the Responsibilities of Feminist Criticism (in Shakespeare

& The Question of Theory p. 238.

[3] On the basis of the same text,

with another text from Mahashweta devi alternative theatre director Parnab

Mukherjee experienced “Ophelia and O” connecting the women

all over the world referring Steven Bercoff’s “The Secret Love Life of Ophelia”

as a sub-text.

[4] Grant H Kester uses these

terms referring British artist Peter Dunn, See introduction of Grant H Kester, Conversation

Pieces: Community + Communication in Modern Art.

[5] "The time is out

of joint; O cursed spite! /that ever I was born to set it right!"

[I.V.211-2].

[6] Hamlet, appears

with a book in his hand. Act 2 scene 2

When Polonius, the chief adviser of Denmark ,

Ophelia’s Father asks: what are you reading

He says: Words Words Words

In 2007 another Hamlet studying in FineArts

Faculty, MSU would say

Images Images Images

[7] Reference: Jean Baudrillard, Images

are Devil Demon, or, The Ecstasy of Communbication (1988,

collected from Semiotext in Post Modernism: Critical

Concepts, edited by Victor E Taylor and Charles E Winquist, p.41-47)

[8] I know one Ophelia,

who lives in a place named Dhakuria, Kolkata, in a three storied building. She

is very much loyal to her parents, loving to her brother.

Whenever she gets a time she goes up to the terrace.

Why does she do so?

I also know a Hamlet, residing in a flat in Fatehgunj, Baroda . He also uses to

go to the terrace.

Ophelia, after following all the loyal obedience to her parents,

all the responsibilities to her loving brother goes to the terrace to grasp the

cityscape. Only from the terrace the most possible view of the city she can

consume, which can metaphorically satisfy her suppressed desire.

The hamlet in Fatehgunj goes to the terrace to peep through the numerous windows of neighbor flats and slams and to voyeuristically enjoy other’s lives.

Once he gets a time to ask

Ophelia: “How are you, are you happy, Ophelia?”

But it is too late.

[10] The Rumbling has

grown quiet.

I walk out on the stage.

Leaning against a door jamb,

I tried to catch in a distant echo

What will happen in my lifetime.

At me is aimed the murkiness of night;

I’m pinned by a thousand opera glasses.

If only it is possible, Abba, Father,

May this cup be carried past me.

I cherish your stubborn design

And am agreed to play this role.

But now a different drama is underway;

This time, release me.

But the order of the acts has been determined,

And the ending of the journey cannot be averted.

I’m alone; all drowns in Pharisiasm.

To live life is not to cross a field.